Blog/Polling

Focaldata / Prolific UK General Election MRP

We see this as a once-in-a-century election, with the Conservatives - previously on course for a 1997 style defeat at the beginning of the campaign, now facing the potential for fewer than 100 seats come election day if current polling trends continue. They hold only c.60 seats with a margin of greater than 5% points.

Headline Findings

- Focaldata projects a Labour majority of 250 seats based on a probability forecast. This takes into account the likelihood of parties winning in individual seats, with national seat counts calculated via a rounded sum of probabilities in these constituencies.

- The upper and lower range estimates for parties are:

- Labour on 450 (with a lower range of 430 and upper range of 471)

- Conservative on 110 (with a lower range of 86 and upper range of 133)

- Liberal Democrats on 50 (with a lower range of 42 and upper range of 58)

- Scottish National Party on 16 (with a lower range of 12 and upper range of 22)

- Plaid Cymru on 2 (with a lower range of 1 and upper range of 3)

- Green Party on 1 (with a lower range of 0 and upper range of 1)

- Reform UK on 1 (with a lower range of 0 and upper range of 3)

- The implied national vote shares are Labour on 41.4%, Conservatives on 23.0%, Reform UK on 15.5%, Liberal Democrats on 11.3%, Green on 5.2%, SNP on 2.5%, Plaid Cymru 0.4% and other on 0.6%

- We find that 109 seats are ‘marginal’, a term we use throughout to denote a seat in which the difference between the first and second largest parties by vote share is less than 5 percentage points. Marginality pinches the Conservatives the most, with the party defending a total 52 seats with a <0.05 margin (just under half of its projected total). A further 16 seats, most of them nominal 2019 Conservative wins, we consider too close to call.

- Most notably, our model projects 28 seats in which Reform UK achieve over a quarter (25%) of the vote share, but only 1 marginal (Exmouth and Exeter East). We have Reform UK on 29% in Clacton, but losing out to the Conservatives on 38%. However, our probabilistic seat counts suggest Reform UK are likely to win at least one seat across the country come July 4th. Given the direction of the data, we expect this to tick up - potentially significantly - in our final update in election week.

- Looking at specific MPs, our model projects losses for senior Conservative MPs including Jonny Mercer (losing Plymouth Moor view to Labour on a 21-point swing), Grant Shapps (losing to Labour on an 18-point swing in Welwyn Hatfield) and David TC Davies (losing Monmouthshire to Labour on a 17-point swing). Both Jeremy Hunt (Godalming and Ash) and Alex Chalk (Cheltenham) are due to lose their seats to the Liberal Democrats. Meanwhile, both Penny Mordaunt (Portsmouth North) and James Cleverly (Braintree) are currently too close to call, with around 2% separating them from Labour, and only 3% separating Priti Patel (Witham) from her Labour challenger. Maidenhead, Theresa May’s former constituency, is currently a LibDem/Tory toss-up with a 0.9% margin. Rishi Sunak safely keeps his Richmond and Northallerton seat despite a projected 16-point swing against the conservatives with a 13% margin of victory.

Findings

The Focaldata/Prolific projection has Labour winning 450 seats across England, Wales and Scotland. Labour is forecasted to make 250 gains, including the entire Red Wall and 4 Blue Wall seats. Conservative losses are peppered across the country, with the largest drops in vote share compared to national 2019 Conservative results in Aldridge-Brownhills (-38.3pp), South Basildon and East Thurrock (-36.5pp) and Cannock Chase (-36.2pp).

Our view is that probabilistic seat counts are the correct way to assess parties’ overall likely seat counts. This is because these Bayesian probabilistic estimates help to quantify the distribution of uncertainty across the estimates and arrive at a better understanding of the range of potential results.

However, we have also produced point estimates for individual seats. These ‘first-past-the-post’ estimates are there to help digest seat-by-seat wins and losses and provide a “clear winner” for each constituency. By estimating individual party vote shares, we can also come to a clearer view of the number of individual seats that are both in play and too close to call. In our analysis, marginals are defined as seats where the difference between the winning party and nearest opposition is less than 5%.

Marginality

The way to understand the Tory seat count is really to see its “strong vote” as its locked-in seats - with a huge degree of volatility or uncertainty about the proportion of “marginal” seats it actually wins. Based on trend lines it is likely that a good proportion might lose come election day. Looking at the exhibit below, it is clear that Labour are on course for a sizeable majority, but the vulnerability of a large chunk of Conservative seats to other parties closing on their vote share means the final outcome is not yet guaranteed. In our estimation, 52 Conservative seats are marginal - of which 39 are a tug-of-war with Labour.

Taking a historical view, this level of marginality is unprecedented. For reference, in 2019, 10% of seats of the 632 constituencies outside Northern Ireland were marginal at the 5% threshold. The figure was 14% in 2017, and 9% in 2015. If the results play out according to our model, a full 17% of constituencies will be.

Reform

Reform has climbed in the polls in recent weeks, reaching a vote share of 16% in our most recent vote intention poll. According to our probabilistic seat counts, we expect Reform to win a seat. However, looking at the individual seat projections, we find Reform in second-place in 101 seats but ahead in none, with only Exmouth and Exeter East a genuine toss-up between Reform and the Conservatives.

Liberal Democrats

Our model has the Liberal Democrats winning 50 seats - a few short of the 57 seats won by Nick Clegg in 2010. However, only 36 of these are ‘locked in’, with a large majority of the remainder in clear toss-ups with the Conservatives - mainly across the home counties. Surrey Heath is a knife-edge with 0.1pp separating the Lib Dems and Conservatives, followed by Tunbridge Wells (2pp), Farnham and Bordon (2pp) and Wokingham (4pp). Outside the South of England, the LibDems are currently defending a projected win in North East Fife from the SNP.

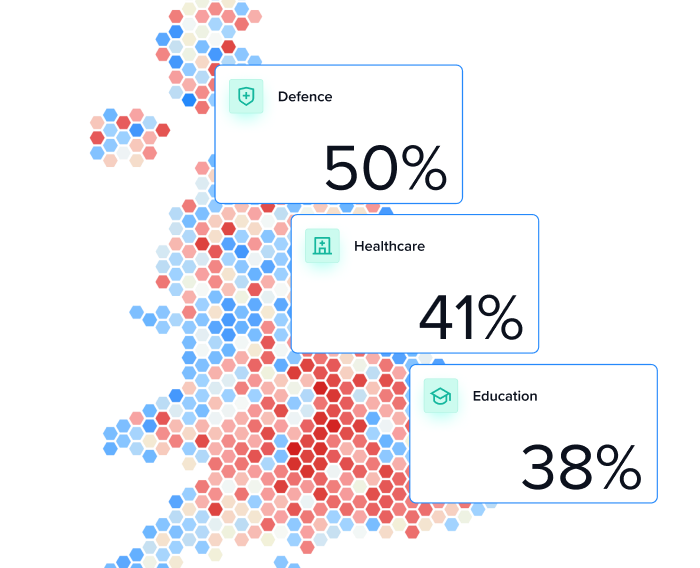

Demographic Findings

Turning to demographics, we find that the Conservatives are gaining just half of voters who recalled voting for the party in 2019, with the remainder split in multiple directions – 1-in-4 are going to Reform UK, roughly 1-in-6 opt for Labour, and 1-in-16 go to the Liberal Democrats. The government finds themselves squeezed by both sides, with 25% losses to their right, and 23% moving to their left.

We see evidence of tactical voting in our voter flows. While only 4% of Labour’s vote has moved to the Liberal Democrats, that figure surges to 18% in Conservative-held seats where the Liberal Democrats got more than 20% of the vote last time around. Likewise, Lib Dem to Labour transfers climb to 26% in Conservative-held seats where Labour got more than 20% in 2019.

Britain’s young voters (and those who did not vote or don’t know how they voted in 2019) break materially for Labour, with Keir Starmer’s party taking 47% of the vote. Notably, this is not just a function of young voters coming into the electorate; excluding 18-to-24 year olds from the calculation still sees 44% of 2019 non-voters going to Labour. Reform UK are picking up a substantial share of previous non-voters, with 20% of non-voters aged 25+ opting for Nigel Farage’s party. We must stress that it’s important to caveat this figure with the possibility that a sizeable share of 2019 Conservatives who have switched parties now say they do not remember how they voted last time.

Up in Scotland, while we expect the SNP to lose a large number of seats, their vote is not fragmenting in the same way the Conservatives’ is. The party retains 63% of their 2019 vote, but Labour (22%) is the only other party picking up more than 5%. Speaking long-term, this gives the SNP a solid base from which to recover in the event the next Labour government becomes less popular.

Looking at age breakdowns, Labour leads with all working-age groups, and quite comfortably. The crossover age at which a voter becomes more likely to vote Conservative than Labour is 68, 24 years higher than the 2019 figure. With voters under the age of 50, no other party breaks the 20% mark.

Middle-aged voters are the key swing group at this election. The government is holding on to fewer than half of their 2019 voters in the 40–65 age bracket, with Reform the biggest beneficiary. Among 2019 Conservatives under 40, Labour are the main alternative.

Labour leads with degree- and non-degree holders alike, with 46% of the vote share among the former and 39% with the latter. Reform has the largest educational split of any party, with almost twice as many of those without degrees (18%) supporting the party (vs. 10% among degree holders).

Majorities of 2016 Remainers and non-voters back Labour, but eight years on from the EU referendum, Leavers are split three ways. This is the opposite dynamic to 2019, when Leavers more or less united behind Boris Johnson’s Conservatives.

In terms of population density, the Conservatives only lead in the most rural parts of England and Wales, but no party clears 35% in total in those areas. As a result, many rural seats are projected to be three-or-more-way marginals, including Brecon, Radnor and Cwm Tawe; Ceredigion Preseli; and Caerfyrddin in Wales, and Skipton and Ripon; Torridge and Tavistock; and Waveney Valley in England.

Data for all constituencies is available here.

How might we be wrong?

#1 Unwinding adjustment is too aggressive

We deploy an adjustment - which YouGov coined as “unwinding”. This adjustment seeks to cater for some of the historical problems with MRP and regularisation and attenuation. We think it’s best to be really transparent about how material this adjustment is. Our model learns from past election distributions to suppress MRP tendencies to move beyond proportional swing. Our adjustment results in significant change in seat count of c.30-50 seats for the Conservatives, meaning that without it, we would be nearer the lowest ends of MRP forecasts for the Conservatives, and highest for Labour. Our political judgment remains that beyond proportional swing is unlikely - but accept entirely that we don’t know where the “slope” is likely to be between uniform national swing and proportional. The evidence from the 2024 local elections was firmly towards, if not entirely proportional. Please see a long-form discussion of this here. If our estimates were entirely proportional for these set of estimates we estimate the Conservative seat count would be c.20 seats lower.

However, even with unwinding, looking at the marginality of seats the Conservatives only hold c.60 seats safely with a margin of over 5% - and are acutely vulnerable to change in vote share up to election day. Labour by contrast hold c.410+ with a margin of over 5%. This is a staggering difference. We are not forecasting c.60 seats for the Conservatives but it is entirely reasonable to assume this could happen - if our unwinding adjustment has been too aggressive.

#2 Fieldwork is too late

The other potential source of error is our fieldwork dates. Interviewing people from the 3rd June - 20th we will miss the late political movement. This campaign, like 2017, has been a campaign of great “change”. From D-Day, to Nigel Farage’s takeover of the Reform party, and the betting scandal, vote shares for all parties have shown material and real change, even when put through MRP modeling. We are assessing whether to release a final updated model given how steep the fall in the Conservative vote share has been since the campaign beginning where the Government was set to lose in a fashion similar to 1997. They could face the prospect of going well below 100 seats, and towards 70 and face their own 1931 super-defeat.

#3 Tactical voting

We have tactical voting effects in the model, but acknowledge that there is great uncertainty over the Liberal Democrat specific seat gains. We had a much larger MRP sample size previously, but due to campaign poll movements have had to drop a significant proportion of it due to it being too historic for the political volatility. The cost of this is we may miss some nuance with tactical voting patterns which our larger previous sizes of 30-50,000 gave us.

#4 Change in turnout patterns

Our validated turnout model uses historic voting patterns going back to 2015. Should the turnout patterns of the electorate change in a material and drastic manner - particularly around youth turnout and older voter abstention we could be overestimating the Conservative vote.

#5 Minor party vote distribution patterns

MRP can struggle with minor parties - and particularly can suppress the vote shares of smaller parties at the top end of the scale. There is a strong possibility that our model may be doing this for Liberal Democrats, Greens and Reform. Should this be the case we can envisage a scenario where the Liberals exceed our 50 forecast, Greens go beyond 1 and Reform realistically target 2-5 seats. An extension of this is where there are prominent independents - our model could, not may not underplay significant vote shares for independents running in more diverse constituencies challenging Labour from the left.

FAQs

What is multilevel regression with poststratification (MRP)?

Multi-level regression with poststratification (MRP) is a statistical technique for estimating public opinion in small geographic areas or sub-groups using national opinion surveys. It originated in America, and was used by academics to estimate state-level opinion cheaply, given the expense of doing polls throughout the country.

MRP has two main elements. The first is to use a survey to build a multi-level regression model that predicts opinion (or any quantity of interest) from certain variables, normally demographics. The second is to weight (post-stratify) your results by the relevant population frequency, to get population level (or constituency level) estimates.

At the end of this process the aim is to get more accurate, more granular (thus more actionable) estimates of public opinion than traditional polling. There are, however, significant technical challenges to implementing it effectively. These include large data requirements, dedicated cloud computing resources, and an understanding of Bayesian statistics.

Why are everyone’s forecasts so different?

Thankfully we cover that here in a long-form essay. TL/DR is that every pollster has different vote shares, and the distribution of each party’s vote share - specifically its slope is drastically different between pollsters

Who built the model?

This new UK model was build by Dr Ben Lobo and Dr Adam Higgins. Our modelers received technical support from Dr Pete Logg who led our successful 2019 UK MRP efforts, and Dr Matt Chennells and James Alster and the wider technical team, and domain support from our Chief Executive Justin Ibbett and James Chief Research Officer James Kanagasooriam.

Background to the Focaldata / Prolific MRP

Focaldata was set up to provide high quality and rapid turnaround MRP in 2017. Since then we have conducted thousands of models for hundreds of clients - corporate and political ones. For this election we built up an entirely new MRP model vs our 2019 model - which strongly performed and captured the dynamics of the race and voting shapes efficiently of each party. For this election we have partnered with the firm Prolific to supplement our sample to provide our model with the largest possible sample in a restrained time period given campaign vote share change - to forecast the general election.

The component parts of our UK 2024 “MRP” model was built from scratch include:

- A new poststratification frame built from the England & Wales 2021 Census and recent ONS data incorporating interlocking cells for [Westminster constituency, education level, ethnicity, housing tenure, 2019 voting intention and age]. Scottish poststratification frame pertained to 2011 census data, and was adjusted through proportional fitting to match more recent data (The “P” part of MrP). The frame uses the new constituency boundaries that came into force this election

- We estimate a mutli-level regression model where individual respondents are nested within constituencies, which in turn are nested within synthetic regions. We include individual-level characteristics such as age and past vote as random effects. We also include numerous fixed effects such as constituency-level party vote share or constituency population density.

- We have deployed an “Unwinding” adjustment to the forecasts which uses prior election vote distributions so that forecasts don’t forecast beyond proportional swing. We have written a detailed blog here on this. This adjustment makes no difference to national vote shares implied by MRP, and correlates to - but does not use - the vote distributions observed at the recent 2024 local elections

- New Turnout model which uses the British Election Study 2019 random probability post-election survey which has a validated turnout field; in other words a survey where we know that someone has voted, not just said they would vote. We have adapted our turnout model to bring in this new data, but also include turnout patterns from 2015 and 2017 elections respectively

Other notes about the model

This MRP uses ‘Rallings and Thrasher’ 2019 notional results parliamentary boundaries.

Technical notes

Focaldata interviewed 24,536 British adults across G.B along with our survey partners Prolific from the 3rd June - 20th June 20, 2024.

We provide estimates of each party vote share in each constituency. The estimates show point estimates along with credible intervals i.e. the high and low estimates. To calculate these, following estimation of the multilevel model, we draw 500 samples from the posterior, using the poststratification frame as new data. We then calculate the median, low (5%) and high (95%) confidence intervals. The intervals indicate that according to our model, there is a 90% chance of the outcome lying between the low and high estimate - while the point estimate is the median value across all our 500 draws.

For each constituency, we provide probabilities of a party winning a given seat. These probabilities are the percentage of the 500 draws that the party wins a seat. Our final seat count is calculated by summing the probabilities for each party across all constituencies. This means our seat count takes into account the uncertainty around our estimates for each party in each constituency.

We include a time parameter in our model so that our estimates take into account any temporal changes in vote choice and ensure that our estimates are weighted to the most recent time period.

About Focaldata

We're on a mission to power the world’s understanding of what people think and do.

We research public opinion for data-driven organisations. With Focaldata, decision makers and researchers get the most rigorous data and analysis at 5x the speed — reducing the time to decision while delivering uncommonly actionable insights. We are a team of engineers, data scientists, product specialists and researchers building outstanding technology and next-generation services. Our services are global. We are non-political and non-ideological.

About Prolific

Prolific is a platform that enables researchers to collect high-quality human-powered data at scale.

Using the Prolific platform researchers can target, contact and manage research participants from Prolific’s diverse, vetted and fairly-treated pool – to deliver world-changing research and the next generation of AI.